Alumni Spotlight: Tiana Birrell

Tiana Birrell is a multimedia artist and curator from Massachusetts. She received her MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2017 and her MS in Environmental Humanities from the University of Utah in 2019. She currently resides in Salt Lake City where she investigates the copious amount of water and energy used by data centers in Salt Lake and Utah Valley. Tiana uses photography, video, projections, installations, and performative lectures to consider these questions as well as bring these invisible structures into visibility. She currently explores this issue as the artist-in-residence at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Arts. Her exhibit the weight of a cloud is up until January 8. Tiana was also awarded the 2019 Digital Matters Lab Graduate Fellowship by the University of Utah for her research on the relationship between data centers and water consumption. She recently co-founded PARC, a Utah-based artist collective, and became a Granary Arts Fellow for developing Incubation Period, a virtual exhibition curated during the March 2020 COVID-19 global quarantine.

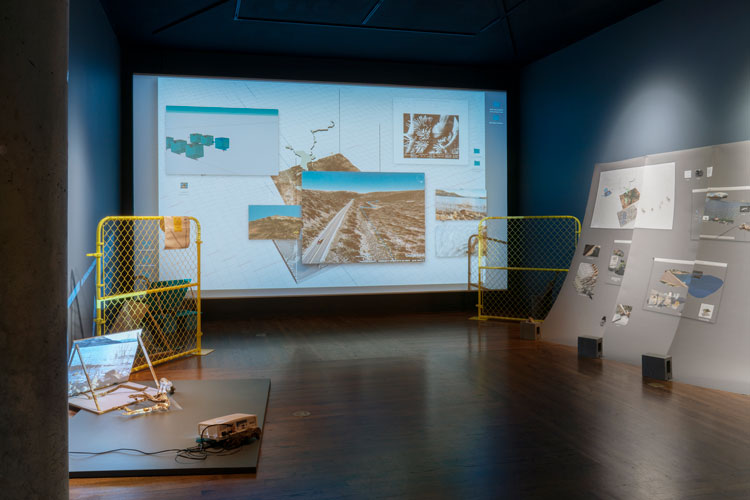

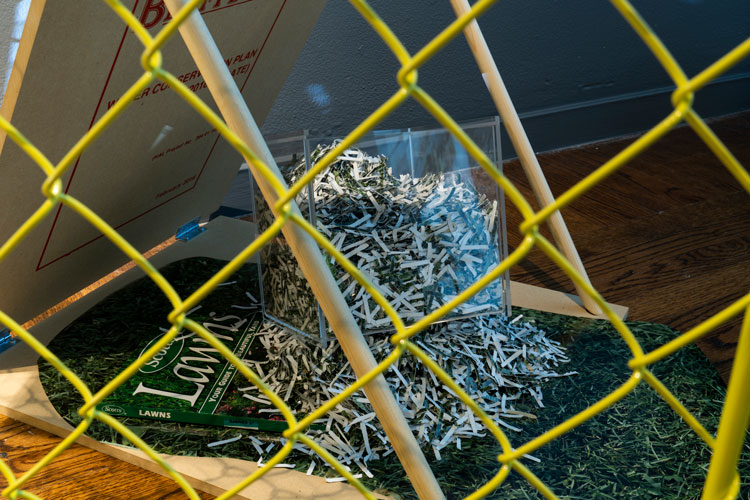

In December 2021, I talked with Tiana about her exhibit the weight of a cloud and how her time in the Environmental Humanities Program informed the project. All exhibit photos in this post are courtesy of UMOCA.

Brooke: What is your exhibit the weight of a cloud about? What questions do you explore? What issues do you address?

Tiana: My work the last five years has been exploring a network of things all related to data: natural resource consumption, landscape, local politics, water, power, data consumption, attention, and the language around screen culture. When I installed my exhibit at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, my hope was to show this complex network while simultaneously honing in to a more specific network. In the weight of a cloud, I wanted to focus on the word ‘cloud’ and unpack what cloud and ‘cloudness’ means in the digital sense, as well as in relation to the fluffy white clouds that we're used to seeing in the sky. I wanted to show their linguistic ties and highlight their similarities and differences. Both the digital cloud and the water vapor cloud rely heavily on water and exist in a physical space. Although we might talk about the digital cloud as a nebulous entity, it actually exists in physical landscapes all over the world and requires immense amount of energy, space, and water to cool its servers. I also wanted to pay close attention to the effect of the digital cloud in Utah, which is where I've been living for several years now and where my research on this topic started at the Environmental Humanities Program. This exhibit is my attempt to represent not only the network of data and data consumption, but to show its relationship to Utah and the specific bodies of water present in this arid state. The title nods to the idea of heaviness, of weight, of materiality, and most importantly, water.

Brooke: This sentence from your exhibit description really stood out to me: The tension between a pithy marketable name, cloud, and the actual cost of resources through colossal water and power consumption illuminates the United States’ complicated relationship between power and land; cybersecurity and natural resources; and surveillance and water rights.

How does art make these tensions visible in ways that an academic paper maybe can't? What mediums do you use in your art to explore these complicated relationships?

Tiana: This sentence encapsulates a significant part of my project and points to one of the larger questions I am asking. What role does naming conventions and language have in perpetuating the narrative of a ‘place-less’ digital world? In this exhibit, I'm not only pointing out the linguistics and nature of the ‘cloud,’ but also a larger digital story. While in the Environmental Humanities program, I made a pictorial encyclopedia of 100 terms that have an analog and digital component. There are several terms in this book that point to Apple and their naming conventions. Why is the Apple Mac called a mac? Why is a mouse called a mouse? Why, when we talk about data, do we think of flow, streaming, and surfing—all terms which have a watery connotation? All of Apple's OSX updates were first named after cats—tiger, mountain lion, and leopard—and now mountains and natural spaces, like Yosemite and Big Sur. What is behind these naming conventions and why are these naturalized components brought into the digital space? The name ‘cloud’ to me is particularly poignant because of its ethereal connotations. When you learn about the water cycle in science class you learn about how evaporation and condensation form clouds, which then, through rainfall, fills up the reservoirs and bodies of water again. With cloud computing, water somewhat evaporates into the air post cooling, but most of the water is brought back into the machine to continue to cool the data centers. Here, water is taken out of the natural water cycle. Pointing this similarity and relationship is important to the project. There is weightiness to that tension. What does the relationship between technology and water mean to the future of our natural resources and the future of climate change in the West?

I was making art prior to coming to the EH Program but I wasn’t convinced it was the right medium and strategy to discuss these complex networks. I came to the EH program thinking I needed to talk about these issues through writing, but once I was in the program it became apparent that materiality would play a significant role in the project. It turns out that a combination of both language and art making ended up being the best way for me to portray this research. Jane Bennett's theory and book Vibrant Matter played a big role in this decision, specifically her theory about how the nonliving world has more agency than is immediately presumed. So much of being an artist is about dealing with materials and material culture. When I'm teaching art or making something, I ask, what does this object mean culturally, politically, scientifically? A simple material can tell a complex story. So, when I am using, let's say, concrete in my exhibit, I'm not just using it because of aesthetic choices necessarily, but because concrete is the material building block of the reservoirs and dams I am studying along the Provo and Jordan River. When you see Plexiglas or glass in my exhibit, I want my audience to see that those materials play a significant role in the story that I'm trying to tell. What is the relationship between glass and screen culture, plastic and flatness? The materiality of the research and the materiality of my artwork start to create a narrative and tell a story of the tensions that surround data and water. the weight of a cloud is my attempt to marry together my interest in words, linguistics, language, as well as the material culture of the 21st century.

Brooke: How did you choose to focus specifically on the National Security Administration data center? How is the military and cybersecurity another layer in this conversation around water, natural resources, and digital storage?

Tiana: When I was pursuing my MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I took a class where we examined the use of technological tools throughout art history. I became more aware of the digital tools that I was materially surrounding myself with, data centers being one of them. I started by researching data centers in general and found myself in Virginia, North Carolina, Nevada, and Utah. I found it strange that a lot of these data centers were located in more arid climates, which makes sense if you consider how much space is required to build a data center. However, if you consider how much water, materials, and energy is required to run these facilities, it seems counter-intuitive to build them in a desert landscape. So why are they being built in these arid landscapes? I had previous connections to Utah and was aware of its dry climate and politics around water, so the data centers there stood out. Once I found out that the NSA was located in Utah, that their facility was the second biggest in the country at about 1.1 million square feet, and that they use anywhere from 1.7 million to 6 million gallons of water a day to cool the servers, it became apparent that this data center would become a critical part of my research. My interest piqued because this tension not only created space to discuss water and resources, but all of a sudden, this whole other conversation about the digital in privacy and surveillance and the military industrial complex arose. I think it quickly became clear that the NSA data center should be my case study, which is actually why I applied to the EH program, I thought I needed to be back in Utah in order to properly go about this research.

Having lived in the West before, but not being from here, I realized how much water equals power. Those who have access to water have access to power. But often, we erase different cultures who previously had access to this land and water. The West is just full of stories of Indigenous populations being completely erased. Often those who have access to water are the ones writing the dominant story. So, when I found this information about the NSA not only being a surveillance machine, but also a water sucking panopticon, new dimensions arose, and it became important to me to tell this story. As an artist, I am constantly looking for that tension. One of the things that I admire about artists and art is its ability to illuminate something that has been erased. Because of the visual nature of art, new connections can arise in stories that were previously invisible. By creating a visual representation of this story about water, power, and natural resources, and sending it out to the public, I feel relieved that perhaps we can take this story and ask, what do we do with this new information? How do Utahns vote differently about water rights? One of the reasons why the NSA is here is because Utah has the second cheapest water in the state per thousand gallons. So, the more gallons you use, the cheaper your water is. The NSA is shrouded in secrecy, but you can almost tell how much surveillance and how much hacking is being done by how much water is being used. That became another interesting way to look at how water can be a carrier of a story, how water can be a carrier of power.

Brooke: What do you hope people think about or do after experiencing your exhibit? Do you have a call to action?

Tiana: Due to UMOCA’s expansive audience, I questioned how I could provide a layered approach to information dissemination. While I was in the EH Program, I did an internship with Save Our Canyons, and I did a lot of tabling for them. This experience helped me understand how to better cater the information I was sharing to a broader audience. When we set up for the tabling events, we brought a variety of materials anticipating that we would be speaking to a wide range of people with various interests and backgrounds. We not only provided information about what we were petitioning for, but we also provided a variety of materials that would allow us to connect with whoever we might speak with: maps, stickers, rocks from the mountains, and a book of wildlife photography made by a local artist who photographs the Wasatch Range. When someone approached our table, I tried get a feel for their interests. If they were politically engaged, I pointed them to the petitions. When a little kid approached, we looked at the rocks and talked about why they liked nature.

When I was preparing for my show at UMOCA, I thought, how can I have a multi-layered experience for my audience? My exhibit can be something political and it can become a call to action if the amount of water used by data centers incites fury in the viewer. Or it can be a place where someone realizes that data, water, and energy are all linked together. Perhaps it causes someone to think about their streaming habits or not saving everything to the cloud. Or maybe the exhibit will just spark questions like, why do I use my digital surfaces so much? Why do I constantly feel the need to be engaged in the digital? You could also go to the exhibit and listen to the water and just feel calm and present, a feeling that I often don't feel when I'm on my screen all the time. So, maybe they leave the exhibit with a call to go out and enjoy nature, whether that be wilderness, a park, or a house plant. I have my own political beliefs; I have my own opinions and ways that I engage. But I think the EH Program helped me figure out how to talk to people with differing opinions and still allow conversations to be had.

Brooke: How did your research and project in the Environmental Humanities Program inform your current residency and exhibit at UMOCA? How were you able to merge humanities research with art during your time in the program?

Tiana: I think I left EH asking, how do I talk to a general public that comes from so many different backgrounds? It's not news that art can tell a story, that words can tell a story. But how do I combine those two elements? That's part of my practice. I feel like I'm partial writer, partial maker of physical objects. It seemed important that the project I started in EH left the academic circle, even though it was born there. It needed to leave that and go out into the public, and it needed to be in Utah. Having the exhibit in Salt Lake or Utah County was important because that's where the majority of these data centers are located and where the water bodies that I'm researching are located. EH informed the way I gave my lecture at UMOCA. It was important for me to have a call to action. So, I was asking, what do we do locally to bring about change? What does change look like for you?

I can't speak highly enough of the EH Program. I'm a multimedia artist, and I come from multiple disciplines. I come from art and anthropology and science. You go to these different programs, and they say they're multidisciplinary, but there's still a lot of hoops you have to jump through. So, when I found the EH Program, it was attractive to me that it wasn't housed in one specific department, that you have professors who are in the law department, who are in English, who are in art, who are in the bookmaking sector. So many different backgrounds come together in the program. And, to me, that's where change will occur. Change happens when you bring in people from different backgrounds to have these conversations. I wouldn't have been able to do this project if it weren't for that element of EH. Within my first week in the program, I talked to a law professor, an English professor, someone who was more involved in activism, and someone who had written a book about water in the West from a geologic standpoint. The resources were so accessible if you sought them out. I was able to take an Independent Study with an art professor who ended up being on my committee. I also did the digital matters fellowship in the library, which was so informative, and that committee is made up of so many different departments. I think the way that the professors take care of their students and send a ton of different resources was helpful. There were always events and opportunities that brought these hybridizations together, and that's where I thrive.

Brooke: What else are you working on right now?

Tiana: EH helped me to think about what role I want to have in the community. I would love to start a residency or an art center where I can continue that space for different silos to come together. And when I say an art center, I also mean that quite broadly. It can be the material arts, the fine arts, but also maybe it's a space where people do poetry readings or writing workshops. I'm just such a huge advocate for creativity in general. So that's where my attention has been lately, trying to figure out how to start a nonprofit. I just moved up to Logan and Cache County. I'm thinking about how I find a community up there and how I create a community. So that's exciting. I've also started gathering resources to start a publication. We'll bring in writing and the arts together in a quarterly publication that people can either get in digital copies or physical copies. I just got the brand identity designed, so that's exciting.

Brooke: What advice do you have for current EH students?

Tiana: Ask a lot of questions. Be comfortable with not knowing answers. For me, it's important to follow my attention. Where do I really want to exist? Because I think when we're still formulating what we want to do, it's easy to get inspiration from a lot of different places. It's wonderful to see what this person's doing and where their journey has led them. But at the end of the day, for me, it was really important to center myself and ask, where do I see myself? Where am I constantly feeling pulled towards? And then try to follow that journey with resilience and determination. Because there are always stumbling blocks that can come in your path. But if you're following your passion and following this internal pull towards what you want to do, that's where the biggest fruits are. Also, reach out to your community. Meet up for coffee every week and talk about questions and ideas. Go for a walk. In school, it's easy to get stuck in this mentality that's like, ‘I have to be in the library, and I have to be reading.’ But at the end of every week, Jeff was like, ‘Make sure you're going outside.’ My cohort always talked about how it's kind of ironic that we're reading about the natural world, but we're stuck behind a screen writing and reading all the time. So it was so wonderful to have the program director reminding us to go out and touch the natural world and remind yourself why you're here in this program.