Alumni Spotlight: Jack Stauss

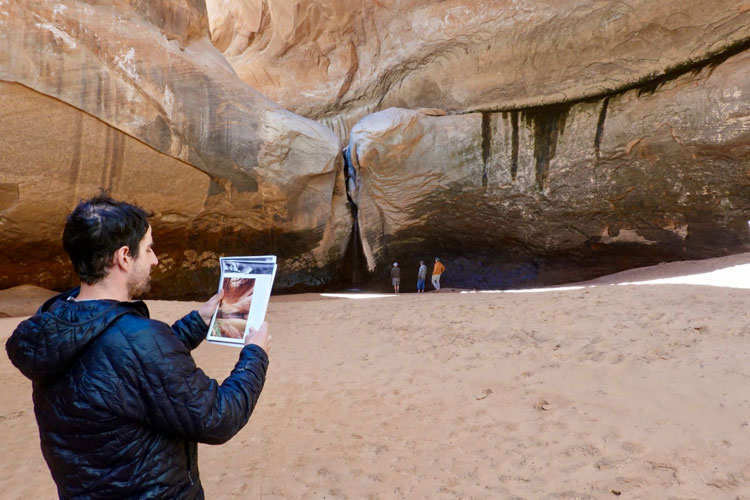

Jack Stauss graduated from the Environmental Humanities Program in 2016. Since then, he has been working for the Glen Canyon Institute (GCI), which is a non-profit organization dedicated to the restoration of Glen Canyon and a free flowing Colorado River. Due to drought, Lake Powell has dropped significantly, and parts of Glen Canyon that were previously drowned are now reemerging. This has created interesting opportunities for Jack and GCI, and their work was recently featured in the Salt Lake Tribune. In July 2021, I sat down with Jack and dove into this pressing issue. We also talked about the ways EH prepared Jack for his current work, favorite memories from EH, and advice for current students. All photos in post are courtesy of Jack Stauss.

Brooke: What have you been up to since you graduated from EH? What work are you currently doing with the Glen Canyon Institute?

Jack: Somehow it has already been five years. I graduated in 2016. I've been at the Glen Canyon Institute almost the whole time. I started at GCI as the office manager, and after the first year and a half, I was promoted to outreach coordinator. I started working all the events that we planned, from talking at public events to tabling at farmers markets. Then for the last year and a half, I have been the outreach director, which gives me more autonomy in planning and carrying out events and communications. I take people to the desert and hold events locally and in cities throughout the Colorado River Basin. The work incorporates all the things that I am good at and love. The environmental ethos that I learned in EH and fostered throughout my time in the West has always been central to my profession, be it working in the service industry to now working at an environmental nonprofit.

When I first started at GCI, it was sort of still this theoretical goal to restore Glen Canyon. That has been this big picture, long term environmental fight that stems from the environmental movement of the ‘50s and ‘60s, the Katie Lee and David Brower type mentalities. For a while, our work looked like reading articles, writing articles, trying to build some buzz around the place. But then, of course, with this drought that has been parching the Colorado River Basin for the past few years, we've been able to see parts of the canyon return from underneath reservoir Powell. The work to restore Glen Canyon had been like a long, slow ride. And then in the last year, suddenly so much is happening so quickly. Recently we’ve had a lot of good media and research trips. We also bring researchers down to the reservoir and look at a specific issue like biological succession, sediment transport, or water storage. We'll bring scientists down to study one of those issues, and then I go out and tell the public about it and we get media published. We’re building a case for why this place is more valuable out of water than inundated with water.

The drought is sort of a double-edged sword. It's scary that the Colorado River, which supplies water to 40 million people, is running so low, but it's also giving us an opportunity to not only rethink how we use and store water in the West, but also to help steward Glen Canyon back to a more natural landscape. My work is helping people understand that process through research and partnerships.

Brooke Larsen: I think that ‘double-edged sword’ you mentioned is interesting. There’s this awful drought because of climate change, but as Lake Powell drops, parts of Glen Canyon that were flooded by the dam are now reemerging. What does the future of your work look like with climate change added into the picture?

Jack Stauss: Yeah, it's a really interesting paradox that I have to grapple with, because the reason that our work has been gaining traction is because we're careening towards crisis, which is a scary place to be in the West. But some of the only time that change actually does happen is when all of a sudden decision makers’ hands are forced because of crisis. No one wants to change stuff like this that has been status quo for 60 or 80 years, because that's the way we engineered it in the twentieth century and the big boom of American exceptionalism. We developed our way through all these problems, so we thought, but it turns out that, especially here in the desert, that's just not the way that things work. I think we're having a moment to reassess that approach before we're over the edge.

Climate models are coming out of places like the Center for Colorado River Studies. Decision makers in Colorado who are perceived as kind of entrenched in the norm have all said, we can't keep going the way we have been. The climate models are showing that things are changing really rapidly. So, we, at GCI, have adapted our big picture plan to incorporate that. Our big project that we started a few years ago is called Fill Mead First, which is essentially reoperation of the two-basin system. So instead of having water in two big reservoirs, we put all the water down river in Lake Mead. We believe that would save water and allow for 500 miles of free-flowing Colorado River, which would be an amazing restoration project at a scale we've never seen. Rivers should exist on their own terms.

For the water savings piece, more research needs to be done. We don't really know how much water is lost to evaporation seepage in Powell or Mead. The numbers are all over the place, like ranging anywhere from 30,000 acre feet to 300,000 acre feet. There really has not been any monitoring on Powell since it was built, they just built the dam and were like, great, we filled a reservoir. Now Powell is down to 33% capacity and looking to drop another 55 feet in the next year. So, what are we going to do? Officials keep saying they're going to just prop it up, they’re going to drain the Upper Basin reservoirs, which equate to like a drop in the barrel of the capacity of Powell, so they really don't have a plan. Our goal is to get these different agencies like the National Park Service, Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Land Management, universities, and research institutions that have more resources than we do to just study this more seriously.

Our goal with Fill Mead First is not to take the Glen Canyon Dam down, it's to build new bypass tunnels at river level around the dam so we can essentially strategize for power pool [the minimum lake level at which hydroelectricity can still be produced]. There would be technically a managed river, we would have to allow water and sediment to flow through those tunnels at first in a strategic manner to not totally decimate Grand Canyon. It would be like a five or seven yearlong project of engineering our way through this new river alignment. You can't go below power pool. If we go to dead pool, it's the worst-case scenario, like we would be really SOL. The Bureau of Reclamation is not going to let that happen. They will fill Powell with Upper Basin water if they decide to fill Powell first. That being said, the Lower Basin states are legally allotted water. If they stopped getting what they're supposed to be getting, they'll do a compact call, which means all the water has to go down the river anyways. So, at GCI, we're like, let's just skip that fight. Let's think about this system as one big Colorado Plateau as opposed to an Upper Basin and Lower Basin. Phase three of Fill Mead First is basically letting the river run, so building new bypass tunnels and letting the water flow freely. That would help mitigate some of these power pool / dead pool / how do we get the sediment out questions.

Ninety percent of the reason Powell exists is just for water storage, simply because the Upper Basin does not trust the Lower Basin to give them their allotment should they need it. Eight percent, probably, is hydropower, so energy produced from the turbines at Glen Canyon Dam. Then like two percent is recreation. People talk about houseboating, hydropower, all these big things we're going to lose, but the only reason Powell is there is because there's no trust in the Basin. But we can figure that problem out through good legislation. We don't need a dam to do that. We’re seeing a huge shift in the energy grid with big coal plants coming offline. People think that reservoirs are efficient. They're not. There’s research coming out about methane released from reservoirs, and methane is one of the worst greenhouse gases. Plus, reservoirs destroy this huge ecosystem. The heart of the Colorado Plateau has been decimated by a dam. So, how green is that?

I think we'll see a shift in management. In five years, there will be new interim guidelines, which is basically how they are going to manage the Colorado River for the next 20 years. In that is where we want to see Fill Mead First. With climate change and overuse on a river that was already over allocated to begin with, we can't keep going the status quo. It just doesn't work.

Brooke Larsen: How did your time in EH prepare you for the work you do now? What value does the humanities perspective bring to the work you do?

Jack Stauss: I think back on that a lot actually. I tell people this when I'm guiding a Glen Canyon trip, I'm not a scientist by training. I understand what fluvial geomorphology and evapotranspiration are and how those interact and affect the Basin in general, but I can't exactly explain those processes in the terms that scientists could. But what I can talk about is how those things affect the natural landscape and how humans interact with that landscape. During my time in EH, we talked about human interaction with place, the human-nature divide, and how we can try to start bridging that. I think understanding big, difficult science topics and then putting those issues into terms that anybody can understand and digest is really important. I think EH gave me those tools to look at difficult subjects and be able to explain it to people in everyday settings through narrative, creative nonfiction, poetry, film. I implemented all those techniques in EH, which was really valuable. For my thesis, I interviewed scientists and advocates and business owners, and those interactions with the complex web of voices that engage with these issues helped me ready myself for doing what I do now at GCI.

Brooke Larsen: What are strong memories or key takeaways from your time in EH? What recommendations do you have for current students or recent graduates?

Jack Stauss: I loved my cohort a lot. I still do. We all keep in touch with a text thread and email thread. Some of us share writing or books that we're reading, which is invaluable. I graduated in the spring of 2016, and Trump was elected in November of 2016. So, it was like all of a sudden all this work we had done and issues we learned about were on hyperdrive. I thought, this is the most insane outcome that I could have imagined. I remember talking to Jeff, we went out to dinner that winter, and he was like, it's a great time to be an environmentalist, anything you want to work on you can pick up a hammer and get to work. Having my cohort and the community in EH, Jeff and Cory included, through the Trump years kept me sane and stable. And to now see what they're doing out in the world, to go to Ken Sanders and see Claire's posters in the store, it's really fun to know my friends are working on cool stuff and still care about all these issues.

During my time in EH, we had an amazing trip to Moab in the fall of my first year. That semester was like turbo style. We were taking foundations and reading a book every week and like having these intense conversations in Brett's class, which was one of the coolest classes I've ever taken. Then in October, we went to Moab for a writing and advocacy class. It was all encompassing, we were in class during the week, and then on the weekends we were down in Moab. For a month, it was full on into the issues, the reading, and the landscape. We were here in the Wasatch during the week and down in the desert on the weekends. I'll never forget that period. I look back on it fondly.

The advice I have for people—I go back and forth on this, two sort of conflicting answers. My first semester, I took classes all over the place. I took an eco-eating class and an environmental justice class. I didn't know what I wanted to do my thesis on, basically, so I was just taking a bunch of different courses. I always suggest people sort of survey a variety of classes. But if I were to do EH again, I would zoom in on what I wanted to focus on earlier. I think that gives you better focus and a better arc through the program. As long as you're working hard and working with professors that you vibe with well, you’ll get value out of the program. Also, get out for hikes in the mountains.