Community Engagement Spotlight: Sam Nelson

Second-year EH student Sam Nelson is currently the Environmental Education Intern with TreeUtah. He is working with local schools to help students learn about plants in their community through creative writing and interdisciplinary, place-based curriculum. Sam is originally from Richmond, Virginia, and has lived and taught in many wonderful places, including New Orleans, Washington D.C., and Puebla, Mexico. He graduated from University of Pittsburgh with a B.A. in English Writing. Since then, he has primarily worked in education and elementary schools. He has also worked in conservation and freelance writing. In recent years, he became a full-time tree geek.

As an EH student, Sam seeks to fuse his interests in writing, education, and plant ecology to help children build stronger relationships to land in their communities. He is particularly interested in storytelling from plant perspectives. Native education and literature guide this interest, and he’s excited to share his projects with children through fiction-writing and place-based interdisciplinary lessons.

In October 2021, I talked with Sam about his work with TreeUtah, his interest in trees, and his strategies for educating kids about plants.

Brooke: What are you working on with TreeUtah?

Sam: I am the Environmental Education Intern at TreeUtah where we focus on urban trees and canopies. I'm working on educational programming and creating educational materials around plants and trees for kids. The goal is to help kids in Salt Lake City pay attention to trees in their neighborhoods in new ways. I'm going into schools and doing lessons around plants and tree ecology. The lessons though are not just about plants as objects of study, but rather about our relationships with plants. In addition to that, I'm also planting trees and working on events.

The curriculum I’m developing is interdisciplinary. Sometimes we relegate the disciplines, like science, language arts, mathematics into separate learning blocks, so I'm really interested in how we can fuse these together through ecology. For example, in this curriculum, I'm working with Pacific Heritage Academy and Northwest Middle School, and we're teaching kids how to pay attention to plants. We're building up some background knowledge and some empirical skills to learn about plants using Indigenous epistemologies like relationality to think about how we have relationships with plants, and then flipping the perspective a bit and having students do storytelling from the perspective of those plants. So that's a way kids can creatively engage plants, not just through traditional science studies, but also through language arts, and think about what is it like to be a plant. What does the plant want? Who are the plant’s friends? Who are the plant’s alleged enemies in the area? What are the plant’s relationships to other plants, wildlife, humans? It’s a creative exercise. In that spirit, I'm working with a few partners now and I'm also doing a presentation at the USEE conference about it. I will be looking for more partners in spring if there are teachers or groups that are interested in learning about plants and creatively telling stories from their perspectives.

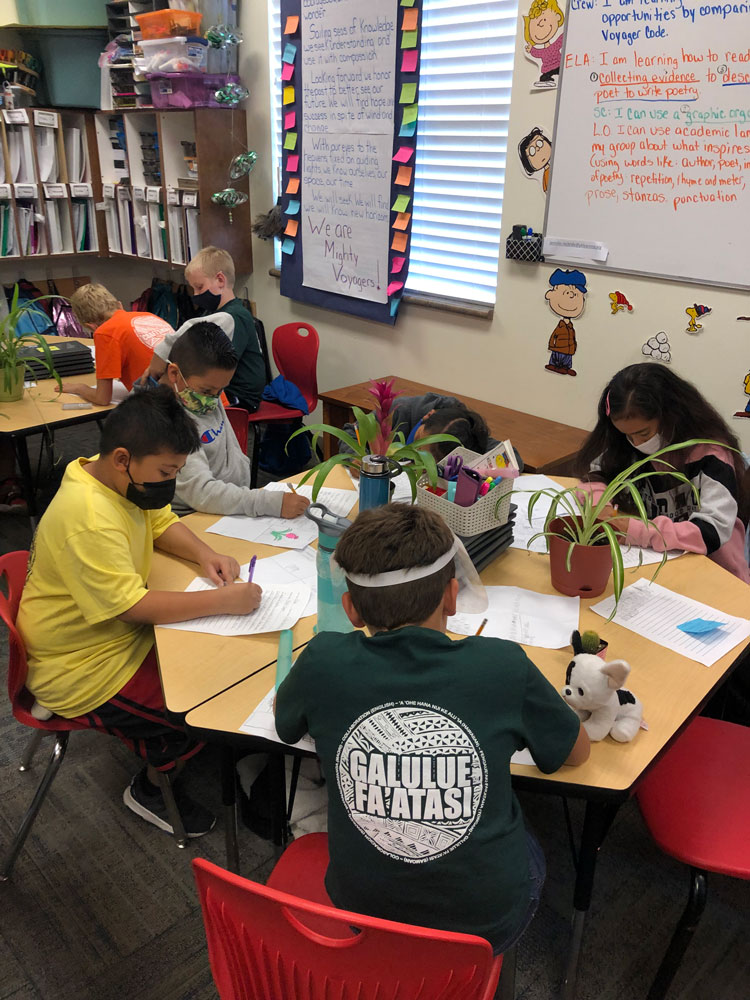

Fourth graders at Pacific Heritage Academy participate in Sam's plant education exercises.

Brooke: How did you develop your interest in trees? Why did you decide to center your community engagement efforts around trees?

Sam: Trees are just really cool. They are the megaflora rock stars of the plant world in my mind. They're highly visible, highly evolved, and interesting. They give me something interesting to think about and look at every day. I've always been drawn to trees since I was a kid when I learned through climbing trees and taking walks in the wood. I took that kind of access for granted growing up. I would say in the last four years, my interest in trees has picked up considerably, though. I started working with Casey Trees in Washington, D.C. I learned so much from the folks there. At the time, I had taken a pause from teaching and had less money, and therefore wasn't doing a lot of traveling. In absence of travel, I started thinking about ways in which I could enjoy my neighborhoods and communities without going out and about. Trees became this interesting touchstone to see something new every single day and push myself to see new details by looking closer rather than moving more widely. Washington, D.C. was an amazing tree city. It just gave me something to delight in every day. From there, I've grown to think about trees as not just something to enjoy, but as an epistemology or touchstone to think about all the different connections in urban ecologies and how all life and beings are connected not just through plants but larger systems. Learning about and spending time among trees became a connection for me to get outside of myself as a singular, egotistical human being encased in my own bitty skull. I think it’s important to note, too, that Native ways of knowing have emphasized these connections and cosmologies looooong before white environmentalists like me started waving our little flags on the importance of this stuff.

Brooke: How have trees been a way for you to connect with the Salt Lake community?

Sam: I've mostly been working in Rose Park with kids. I'm working in Northwest Middle School and Pacific Heritage Academy, Decker Youth Center, as well as additional events with Tree Utah. So, I've been connecting with kids about plants and trees. Trees are our most visible plants, but really the focus of the educational materials is plants themselves. I think one thing I'm trying to do is pointing out that trees and plants are a shared experience we all have. Kids that are in lower income communities are often taught that nature exists somewhere else. There's often been a push to create supplemental outdoors programs, in which we take lower-income kids into the woods, to the Wasatch Mountains, or other places to experience nature and alleged wilderness. Sure, there’s some value to this, but we have a rich, shared experience of plants and trees in any urban community. So rather than taking people outside of their communities to experience nature, I'm working with communities and pointing out what's in their neighborhood that they could pay attention to every single day. It has been fun and interesting, and kids are receptive to it. Some of them initially are more interested in animals because animals are charismatic and lively. But if you plan lessons in ways to show how trees and plants are lively too, I think the kids are incredibly receptive and many intuitively already know this.

Brooke: You have also hosted tree walks and tree plantings. How do those activities build community?

Sam: I did a tree walk on the University campus, and it was a delight. We had about 25 people show up, which on a Wednesday night is a good deal. We had alumni from the University, and some Biology undergrads, and just some interested people that were walking by, so that was great. People asked a lot of questions. The tree walks are an effort in paying attention to trees intentionally instead of relegating them to background theater. Attention is a way in which we reframe how we think about the world we’re moving through. A tree walk is fun in that sense. For one hour, we just think about trees intentionally. Tree planting is similar. A lot of EH students love Robin Wall Kimmerer. One of her themes is not just that we can learn from plants, but that this relationship we have is one of reciprocity. Planting a tree is one of the easiest acts of reciprocity. Well, I don't want to say easiest because it can be pretty hard to plant trees depending on the soil and the tree. But planting a tree is an act of reciprocity. We are giving something back to the environment and ecology by planting a tree that's going to outlive and outlast us. For me, planting a tree is not only an act of reciprocity, it's also an act of humility.

Sam leading a campus tree tour.

Brooke: Before coming to EH, you were a teacher. How does that background inform your current work on tree and plant education?

Sam: I care deeply about children—how we're serving them, how we're working with them, and how we see them. We often see kids as on their way to being humans instead of fully human as they are and appreciating them where they’re at. And I'm disheartened sometimes at the ways we set up education for students, especially for Black and Latinx students who we're often sitting down at desks for eight hours at a time to urgently catch up to suburban white kids and close the so-called 'achievement gap.' It's really an opportunity gap. And sitting at a desk for eight hours is not an opportunity; it’s a crusher. Plants and outdoor spaces, these are teachers too—they're a classroom. I think there are ways in which we can really help students connect to their own rich communities and get them out of this weird push to close the so-called achievement gap, as if that will solve all the issues they’ll face.

I'm also concerned about the way we teach science and the way we teach about climate change. We're either passively teaching students to neglect a whole lot of ecological issues or giving them a lot of anxiety about climate change without giving them helpful tools. I think about plants and trees as a different way to connect with the outdoors, with the environment, with the ecology. I think about climate change not as this boogeyman monster itself, but as a symptom of a deeper problem in terms of our relationship with the environment. So as an educator and a writer, I think about how to resolve that. One way is to rethink education. So instead of teaching kids that climate change is coming, and it’s doomsy and awful, and it's going to get us if we don't fix it, actually, let's address our current relationships with land and plants and talk about the ways in which they've been disrupted for previous peoples, and the ways they’re being disrupted now, and how they might be disrupted in the future. Let’s discuss ways in which they can participate in healthy, reciprocal, and more mature relationships with the land around them. Then let’s see what they do with that as they grow older.

Brooke: When we talk about community engagement, we're often referring to human communities. How are trees also part of our community and how is your work seeking to redefine what we consider community?

Sam: One thing I like about TreeUtah is the mission aims to improve Utah's quality of life through the tree canopy. When I think about quality of life, certainly that's partly about equity in human society, but quality of life can also be about more than humans. Quality of life can be about the ecosystem. Planting trees is helpful for soil, birds, critters, insects, wildlife; it increases the quality of life for all of us that are part of this entangled urban ecosystem and community. So that's something I think about quite a lot. Planting trees reduces our anthropocentric views about living good life. It reframes quality of life as a shared quality; let’s all live better. I know trees are not the only answer to living better, but I also know plants make a lot of life possible. And I’m trying to lean into that more and more.

Categories

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- community engagement (2)

- student (1)

- trees (1)

- environmental education (1)

- plants (1)

- alumni (1)

- forests (1)

- phd (1)

- policy (1)

- collaboration (1)

- governance (1)

- land management (1)

- forest management (1)

- bikes (1)

- bicycling (1)

- advocacy (1)

- faculty (2)

- energy (1)

- nuclear energy (1)

- literature (1)

- film (1)

- art (1)

- leadership (1)

- research professorship (1)

- research (1)

- nuclearism (1)