Alumni Spotlight: Ayja Bounous

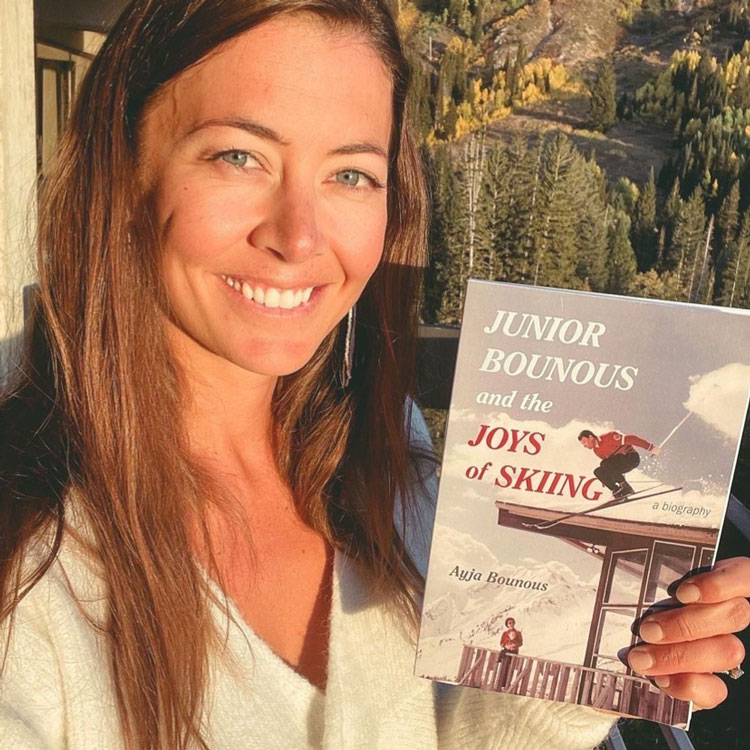

Ayja Bounous grew up at the base of Little Cottonwood Canyon in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah, where the rhythmic pulse of the seasons was as much a part of life as breathing. It was not until her adult years, however, that she realized how her whole world revolved around Wasatch snow—from the places she loved, to the activities that she enjoyed doing, to the relationships in her life. After a 5-year stint in California, where she studied music and environmental science at Santa Clara University, she returned to the Wasatch Front. She earned a Master's of Arts in Environmental Humanities from the University of Utah in 2017, and went on to publish her master’s thesis, Shaped by Snow: Defending the Future of Winter, with Torrey House Press in 2019. She recently published her second book, Junior Bounous and the Joys of Skiing, a biography about her grandfather and his role in the ski industry. In lieu of a desk job, she requires at least 40 hours a week spent outside to keep her happy. (She is broke—and very happy.)

Below are Ayja's written responses to questions about her her two books, thoughts on winter and climate change in Utah, and favorite memories from EH.

In your debut book, Shaped by Snow: Defending the Future of Winter, you examine how your personal relationships are deeply tied to snow and how climate change threatens those relationships. I know you wrote a whole book about this, but give us the summary: what is your relationship to the snow-covered Wasatch Mountains, and how has snow shaped your relationships?

It's no secret that our identities are often defined by the places and environments we grow up and live in. The landscape that most defines me is the Wasatch Range. The Wasatch were created by uplift and erosion by water—in the frozen form of glaciers or as snowmelt in the spring. The physical landscape is shaped by snow. Similarly, my family and the relationships I have with many of those I love are (spoiler alert!) shaped by snow.

Those of us in northern Utah live with the seasonal swing characteristic of this region; from hot and dry summers to what I would consider the perfect type of winter—flurries of storms that bring inches to feet of light powder, bookmarked by bouts of dazzlingly sunny, dry spells before the next storm. Ever since the 1930s, when my grandfather, Junior Bounous, started skiing, my family has been anchored to the snowpack of the Wasatch in more ways than one. I’m the first person in my direct lineage on my father’s side who hasn’t pursued a career in the ski industry; my grandpa, grandma, both parents, sister, uncle, and a smattering of cousins chose this path. The snow-covered mountains are where we work, where we relax and where we exercise, where we find inspiration, and where we spend the most time as a family.

Climate grief is a theme of your book. Where do you sit with this grief now? What emotions come up for you at the start of winter?

I still struggle with climate grief—I don’t know if I ever won’t struggle with that. Every shifting season brings along a new climate-related dread, from diminished snowpacks to wildfires to floods to droughts. But while I still struggle with climate grief, I have more hope now than I did when I was writing Shaped by Snow. I think I credit some of this to the Gen Z activists who have risen up in recent years. While millennials had to struggle to convince our elders and politicians that climate change was real, something that needed to happen before we could really push for change, Gen Z has been able to focus their efforts on frying much larger fish. Dealing with the science since they were born (and having the science relayed to them as hardcore and provable facts rather than mere opinions) they have taken up the fight against fossil fuel companies and their own governments in powerful ways. It’s amazing to see how much more climate change is discussed in mainstream media than when I was in EH, and how the conversations have shifted from containing our personal carbon footprints to suing fossil fuel companies. Where I felt like my grief and anxiety could cause me to freeze in the face of climate catastrophe, it seems that wallowing is not an option for the younger generation—the only option is to fight. And that gives me hope.

How did your experience in the Environmental Humanities Program shape or support this book? What advice do you have to current and future students who want to write a book manuscript as their master’s project?

I’ll never forget how I decided to write this story. It was at the end of my first year in the program, on a trip down to the Rio Mesa Field Station in southern Utah, and my cohort began having conversations about what our theses would look like. Jeff McCarthy and I ended up hiking next to each other for a few hours and through conversation and probing questions the idea started taking shape. From that moment forward my committee helped guide me through the process of finding a story and telling it in a meaningful way. I had wanted to be an author since I was 10 years old, but I would have never been able to do it without the EH program. Had I tried to jump into writing a full-length book on my own, I definitely would have become overwhelmed and given up entirely. As it happened, I didn’t even realize I had written the first draft of a book until after my defense, when Jeff told me that if I worked on editing and lengthening it, I might be able to find a publisher and get it into print. Which is exactly what happened.

My advice to other EH students is to start small. Don’t worry about the length. Don’t force it. Find your story first. It might seem cliché, but search for quality over quantity. Once you’ve discovered your story, you might be surprised how it will seemingly write and expand itself with little effort from you.

You recently published a new book. Congratulations! Junior Bounous and the Joys of Skiing: A Biography is about your grandpa and his role in the ski industry. How did writing this book impact your relationship with your grandpa, as well as your relationship with skiing? What did you learn?

Thank you! This project was something I had dreamed about writing for a long time, and it was only the confidence and experience that came from writing my first book that made this possible, so I have EH to thank for this book, as well.

It’s difficult to find words that can accurately describe how special it was for me to write this book about my grandpa. I’ve always been close to him, but the countless hours we spent together brought us so much closer. I grew up hearing that he was a famous skier, but I never knew why. And discovering the why was what was so magical. As one of the first American-born ski school directors, he is one of the reasons that skiing in the mid-20th century transitioned away from the rigorous European technique (where a skier couldn’t advance in their learning until they had mastered each step perfectly) to what became known as the American Ski Technique, which prioritized enjoyment over technique. It’s an approach that defines most of the ski industry today. As a ski instructor at Alta in the 1940s and 1950s, Junior was also integral in helping develop a technique for skiing powder—considered a strictly American way of skiing at the time.

This book, in many ways, was an extension of Shaped by Snow. It might not address climate change in the same way, but every chapter is determined by Junior’s relationship to a different landscape in his life; growing up on his family’s fruit farm near the base of Provo Canyon; hiking and skiing on Mount Timpanogos; living and working in Little Cottonwood Canyon; dealing with the enormous snowfall at Sugar Bowl Resort in California; experiencing the transition from Glen Canyon to Lake Powell and the recent transition towards Glen Canyon once again; appreciating the delicate beauty of Wasatch wildflowers.

Researching his life has made me feel even more connected to the Wasatch and its winters. I answered your first question by saying my family’s been connected to the Wasatch snowpack since the 1930s, but that’s not necessarily true. In 1901, Junior’s father settled the family orchard at the confluence of three different water sources—all fed by snowmelt. It’s what led the family to become successful farmers (Junior still lives on the same plot of land today) and what gave Junior his first understanding and appreciation of how valuable water is—an appreciation that has run through my family now for five generations. And it’s made me all the more aware of what is at stake if we can’t mitigate climate change.

What issues in the ski industry should people pay attention to this winter? How can winter sports enthusiasts show up in defense of winter?

On a local level, I believe there’s no greater threat to Wasatch snow than the shrinking Great Salt Lake. A section of Shaped by Snow deals with the risks the disappearance of the Great Salt Lake poses, and I had many people approach me after they’d read this section saying, “really? Is this really this much of a threat?”. That was back in 2019, and headlines about the Great Salt Lake were few and far between. It seems as though just in the last year there’s been a surge of public awareness into the issue and not a moment too soon. As the lake bed dries up, the Salt Lake Valley has the potential of becoming a toxic dust bowl. Besides creating poisonous air conditions and decimating bird populations, dust is a snow killer. The layers of dust would land on our fresh snow, causing it to melt quicker, with enormous consequences to our watersheds. The presence of the GSL can also lead to some of the additional snowfall known locally as “lake effect,” which can contribute a few inches of extra snow per storm when the conditions are right (those who skied in the Wasatch during the mid-December storm may have benefitted from this phenomenon!). Winter sports enthusiasts have a lot to lose if the Great Salt Lake becomes an environmental disaster. It’s one of those environmental disasters that’s almost too terrifying to look at directly, but if we want to protect our winters, we must address it—as soon as possible.

Can you imagine how powerful the Wasatch ski community—with all of their combined influence, resources, and passion—could be regarding a local issue like this? How much pressure they could apply on our politicians?

Favorite EH memories?

The time we spent in Centennial Valley is something I still fantasize about (though I leave the mosquitos out of my daydreams) and hope to return to one day. The Rio Mesa station is a close second. When it comes to the most powerful memory from my time at EH, I recall an event that we executed during the fall of my first year. We hosted a community screening in Vernal, Utah. The film, Toby McLeod’s Standing on Sacred Ground, was about the devastating consequences of tar sands mining. Since the U.S.’s first tar sands mine was beginning development outside of Vernal, bringing both harmful environmental consequences as well as jobs, it was a turbulent topic in that community. Despite being told that most people in Vernal were in favor of the mine, the event was standing room only. I’ll never forget the energy during the Q&A portion of the night. It was electric. It felt like a rising tide. The dissent in that room proved the current narrative of fossil fuel companies wrong. That night was evidence that a community so-called reliant on fossil fuels can still be opposed to extracting them. To me, that night solidified how important the humanities and storytelling can be in the climate fight.

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- alumni (4)

- snow (1)

- winter (1)

- climate change (2)

- writing (4)

- creative writing (1)

- book (1)

- memoir (1)

- Great Salt Lake (6)

- symposium (1)

- event (1)

- community engagement (8)

- water (3)

- faculty (5)

- research professor (1)

- history of science (1)

- coevolutionary studies (1)

- American West (1)

- history (1)

- Native history (1)

- public history (1)

- energy (1)

- art (2)

- environmental justice (3)

- just transition (1)

- student (3)

- Great Salt Lake Symposium (1)

- Indigenous (1)

- practitioner-in-residence (2)

- narrative strategy (1)

- political science (1)

- communications (1)

- Mellon Community Fellowship (1)

- environmental health (1)

- air quality (1)

- disability justice (1)

- philosophy (1)

- science (1)

- Anthropocene (1)

- West Desert (1)

- Pony Express (1)

- bicycling (1)

- environmental communication (1)

- queer ecology (1)

- wildfire (1)

- climate communication (1)

- science communication (1)

- forests (1)

- Indigenous sovereignty (1)