Alumni Spotlight: Morgan Lawrence

Through fire, forest, salt, and sky, Morgan Lawrence lives and works to ground herself in the ecosystems of the American West. Morgan graduated from the Environmental Humanities Program in 2021, going through the program during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a current ORISE USDA Climate Change Communications Fellow, she translates climate science and develops communication materials related to climate change in forestry, agriculture, and rangelands. Prior to working at the Northwest Climate Hub, Morgan worked for four years as a wildland firefighter, and for three years as an environmental educator in Rocky Mountain and Denali National Parks. While in the EH Program, Morgan researched the effects of anthropogenic alterations and climate change on the Great Salt Lake ecosystem.

In December, 2021, I talked with Morgan about wildland firefighting, climate change communication, the Great Salt Lake, and the abundance of creative freedom and resources EH offers.

Brooke: What are some highlights since you graduated from the Environmental Humanities Program?

Morgan: I did another season of fire, which I finished in the beginning of October. It was cool after graduate school to have the experience of working a job that I had done before school. The job was super physical, like pick up the heavy log and put it on that side of the creek, kind of elemental stuff. It was interesting to see the effects of what I was doing quickly. Whereas with graduate school, you create this project and you don't always know where it's going to go or if it will have any effect. Once fire season was over, I went straight to the Oak Spring Garden Foundation’s Writing the Landscape course. Which was so cool. It was a week-long course in Upper Ville, Virginia. The owners of the property, Paul and Bunny Mellon, converted an old horse stable into rooms for artists and writers to come to the land. The course was taught by Gretchen Henderson, who formerly taught the Environmental Humanities writing seminar. I received a scholarship, and I hope other EH students also do it in the future. Now, I live in Missoula and I started a job as a climate communications fellow for the USDA Northwest Climate Hub. The position is through this organization called ORISE. It's such an awesome opportunity, and it gives people who are just coming out of graduate degrees the opportunity to work with a federal agency, make good connections, get paid well, have full benefits, and do cool work.

Brooke: How was your experience as a wildland firefighter? How did that shape your interest in your current work with the USDA Northwest Climate Hub?

Morgan: My experience in fire has been largely wonderful. I did four years of fire—three years when I was younger in my early 20s, which culminated in being on a hotshot crew in Colorado, and one season this past year. I took five years off to work in Denali and Rocky Mountain National Parks and go to school. Then I worked as a firefighter again this year because I had this romantic version of what it was like, and I wanted to relive it. I also wanted to make money.

I grew up in Western Montana, in the Bitterroot Valley where there are fires all the time. As a kid, I watched fires ravage the mountains by my house. The field by our house was a heli base one summer, and helicopters were landing there all the time. So, I grew up with fire and this realization that it was something that you had to think about and fear. Also, there were always conversations about fire intensity and severity increasing, and we saw it anecdotally on the landscape actually happening. When I went into fire, I got to experience what wildfire does on many different fronts and watched it burn in front of my eyes. Working fire, like any job where you're working manually, you get to know processes of the landscape that you just wouldn't know otherwise, like the way a fire moves through a Ponderosa compared to a Douglas Fir. I remember specifically a moment when I was 22 and fighting fire. I had just gotten done studying English literature in undergrad, and I didn't really know anything about trees. I remember looking at all these different plants, and as I was digging line, I thought, wow these plants are really cool, I wonder what they are and what they do. That was sort of the beginning of my whole interest in not just environmental issues but in the environment generally.

My dad was super right-wing conservative, and anything environmental was basically a bad word when I was growing up. I didn't realize that I had that interest until I was on my own and working a job where the environment was in front of my face all day, every day. I was like, oh, actually, this is fucking cool, and I want to know more about this. Working as a wildland firefighter impacted every decision I've made since then. My interest in communicating science to the public in a lot of ways comes from fire. I had so many conversations with people back home who had little to no understanding of where fire belonged on the landscape or that there were even different kinds of fire. I realized that we need people who can communicate these things and maybe that's something I can do. That led me to the Environmental Humanities Program and my current job, because a lot of what I'm doing in this job is climate and fire communication.

Watching fire transform from the time I was 10 years old in the Bitterroot to now, it's insane. There is a grass fire in Great Falls today, which is in central Montana, and it burned a bunch of structures. It's December 1st. When I was a kid, that just did not happen in Montana; winter was here on October 19. In my time of living in a fire prone landscape and working in fire, fires have definitely gotten more intense and scarier. That is so clearly climate related to me. Working in fire and realizing how much it's impacting communities in the West and places that I care about has really driven me to a career where I make it my priority to communicate these issues and, more importantly in some ways, communicate that there are things we can do. There's a lot of practices that have been in place for a long time on this land that can prevent intensifying fires from getting worse, or can even make them better. Working in fire and then going to EH led me to a job that's the almost exact embodiment of the two fields.

Brooke: You've found this career path at the intersections of writing, land management, and climate science. How did EH prepare you for that?

Morgan: The Environmental Humanities Program was the best preparation I could have asked for on so many levels. You're just writing all the time in EH, and I remember being in Brett's class and being like, I just can't keep this up, I'm exhausted. And the reading—oh, my god, the amount of reading that we did in this program! But now, in my job, that's literally what I do all day. I read and read and read and read, and then I synthesize it into something that the public can understand. That's a lot of what we did in EH. So, I think in that way, EH is excellent for any career in communication. So much of what you do is take dense science and try to make it into something that's appealing to people who don't want to read dense science. I think that skill of being able to see the nugget of gold in a scientific article and transfer it into something that's more public facing, and maybe more artistic, is the jewel of EH for me. Also, EH gave me the opportunity to explore. I worked in Bill Anderegg's lab for two semesters, and I took a plant ecology class. Having that opportunity to explore science classes in a humanities program was so awesome. I took qualitative methods, which was also excellent, because I interview a lot of people for my current job. The opportunity to take a diversity of courses played in well to this specific job I found. I think the trust that the faculty have in you as a student makes that possible and gives students a lot of confidence to pursue their interests. There's no way I would have my current job if I didn't go to EH, basically. On so many fronts, I'm so grateful to the program.

Brooke: The focus of your master's project was the Great Salt Lake. What specifically were you researching and communicating about the lake? How does it feel now to see the drying Great Salt Lake come up in the news and media?

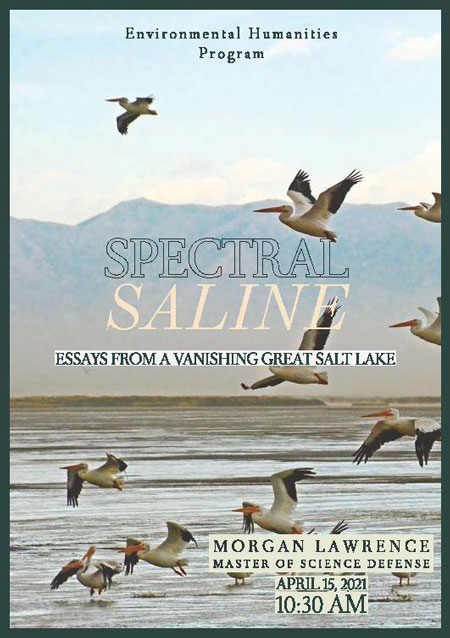

Morgan: My project in EH was basically how anthropogenic changes and climate change have affected the Great Salt Lake ecosystem, particularly as they pertain to American White Pelicans. I wrote a mixed method, environmental history, creative nonfiction piece, about American White Pelicans in the Great Salt Lake. I fell in love with the lake hardcore, and I don't really know why. I didn't even go there that many times before I was like, ‘Yeah, I'm writing about this.’ I remember our first semester, Brett Clark said, ‘You don't have to visit a place to love it.’ At that time, I was like, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’ And then I went to Great Salt Lake, and I was like, well, maybe you don't because I already really love this place. Something about that landscape and the people involved in that landscape just drew me in, especially pelicans are just these lonely but not lonely little creatures out there living on this little island making it by despite all the shit we throw at them. I think I saw Great Salt Lake as this wastelanded space, this place that had been just so heavily polluted and abused, but still contained so much beauty, intrigue, history, and current cultural connection. I don't know how everyone doesn't want to write about it. It's so cool. It has so many dichotomies in the way that it exists.

I wrote about what I loved, and EH gave me the freedom to do that. I can't imagine any other program that has the creative freedom and resources that EH gave me. You get to follow your passion in these ways that you just never expect and come out with this project that you're proud of. It's not perfect, but you love it. I loved my project. I was talking to Jaimi Butler at the Great Salt Lake Institute this morning. We're expanding on my project, and we're trying to do this other series about women in the lake. I feel like it's so easy to build on your project in EH because it's something that you love, at least for most people.

How do I feel about Great Salt Lake popping up in the news so much? Actually, I feel great, because harm has been happening to Great Salt Lake for a long time, and I’m happy it’s finally getting attention. Cities and towns along the Wasatch Front were dumping raw sewage into the lake until the 1960s. There are two Superfund sites on the edge of the lake, and they've been leaching toxic chemicals into the lake for God knows how long. All of these birds are dying for various reasons. This has been happening for a long time. People think, ‘Oh, there was flooding in the 80s, so that means that the lake is fine, and we don't need to give it any water.’ In the 50s and 60s, city council members of Layton were writing newspaper articles that literally said, ‘We want to run the lake dry. We want not a drop of water to go to the lake.’ Literally they said this, non-ironically. That was not an evil thing to say back then, the thought was like, ‘Nope, we want all the freshwater for people because we are Zionising the desert.’ I think that it's cool to see how much that ideology has shifted. While they were comfortable writing articles like that in the 50s, now the articles are being written by people like Brian Maffly, and they tell the truth about the Great Salt Lake being at its lowest level ever in recorded history and what might be done to save the lake. Now on Instagram, there's Save Our Great Salt Lake. I don't know who's running that, but whoever is doing it is doing an awesome job. It is so cool to see people caring that much. Everyone's sharing on Instagram, ‘Go to this city council meeting, sign this petition,’ and I'm like, ‘Oh, my God!’ Even last year, when I was working on my thesis, none of this stuff was out there.

I don't think the problem was lack of love, or a lack of interest, people just didn't have access to information. But there has been an intentional effort to shift attention away from the lake for a long time. The City Council and the Utah Office of Tourism intentionally shifted people’s focus to the Wasatch Mountains. With that shift, the lake became this place that could be easily polluted, and nobody had to give a shit about it. But now people are like, ‘Wait, what the hell's going on in the lake? There's aerosolization of toxic chemicals? That’s not cool.’ So, it's great to see people really caring about the lake, and lots of different kinds of people caring about it. I'm super happy it's gaining traction.

Mono Lake is a good example of what could happen with Great Salt Lake if this interest and engagement continues. Mono Lake was preserved at a certain elevation. Mono Lake is this awesome lake in eastern California. It's a saline lake too, and it also has brine shrimp. There's a lot of similarities with Great Salt Lake. It was at historic lows in the 1960s. There were some students from UC Davis that came in and advocated for the lake, and through their grassroots efforts, Mono Lake was protected. It was lowering because of water diversions, mainly to Los Angeles. So, the government protected Mono Lake at a certain elevation. It still hasn't reached that elevation 40 years later, but it has come up a lot, like 10 or 15 feet. I could see Great Salt Lake also being preserved at a certain elevation. I think that's critically important.

Maybe I'm being hopeful here, but I don't see a future in which the Great Salt Lake is not protected at all. I think there's too much interest in preserving this place. Eighty percent of Utah's wetlands are on the shores of Great Salt Lake. If we kill this place, we kill these birds. Beyond that, people are realizing that this is a public health concern, and not just a public health concern for people that the legislature often doesn't care about, but a public health concern for like wealthy people who live high up in the Avenues. It's ubiquitous in its effect. I think that there's a good chance that the lake is going to be protected in some way, although I'm sure it's not going to be at the level that will make me satisfied or Jaimi Butler satisfied or anyone who really loves the lake satisfied. I don't feel that I played a role in the Great Salt Lake getting the attention that it deserves, but I do feel honored to have knowledge of it as it happens. In graduate school, I was frustrated that more people didn't care about this. I'm not blaming anyone, but we barely talked about Great Salt Lake, and it's like this massive ecosystem we can see from campus. I feel like that will not happen anymore, and it's all because of people making an effort to care about a place.

Brooke: What advice do you have for current EH students?

Morgan: Trust your gut when it comes to your thesis. When I came in to the program, I thought I wanted to write about the desert. I love the desert, so I was really pushing that internally and externally. Then I started doing research into Great Salt Lake and somewhere in my little heart, it said, ‘You should do this. You want to do this.’ I resisted that voice so hard for a couple of months. But eventually I realized that all the pieces were coming together. It was not only the easier project because of proximity and connections, but it was also the project to which my gut was saying, ‘Yes.’ Initially, I thought that the thesis idea you started with had to be the one you finished, and that is just not the case at all. I had to grow into the spot where I decided, and then when I decided, it was like, phew, obviously, this is what I was supposed to do. But to reach that point, I had to acknowledge my gut instinct. Don't stress out too much about picking your thesis or project right away. Let it come to you, because it will.

Categories

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- alumni (4)

- snow (1)

- winter (1)

- climate change (2)

- writing (4)

- creative writing (1)

- book (1)

- memoir (1)

- Great Salt Lake (6)

- symposium (1)

- event (1)

- community engagement (8)

- water (3)

- faculty (5)

- research professor (1)

- history of science (1)

- coevolutionary studies (1)

- American West (1)

- history (1)

- Native history (1)

- public history (1)

- energy (1)

- art (2)

- environmental justice (3)

- just transition (1)

- student (3)

- Great Salt Lake Symposium (1)

- Indigenous (1)

- practitioner-in-residence (2)

- narrative strategy (1)

- political science (1)

- communications (1)

- Mellon Community Fellowship (1)

- environmental health (1)

- air quality (1)

- disability justice (1)

- philosophy (1)

- science (1)

- Anthropocene (1)

- West Desert (1)

- Pony Express (1)

- bicycling (1)

- environmental communication (1)

- queer ecology (1)

- wildfire (1)

- climate communication (1)

- science communication (1)

- forests (1)

- Indigenous sovereignty (1)