Faculty Feature: Gregory E. Smoak

As Director of the American West Center and Associate Professor of History at the University of Utah, Dr. Gregory E. Smoak specializes in American Indian, American Western, Environmental, and Public History. As a publicly engaged historian, he has worked on projects for the National Park Service and the United States Forest Service, as well as numerous Native peoples including the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Big Sandy Rancheria of Western Mono Indians, and the Navajo Nation. Greg is the Utah Humanities State Scholar for Think Water Utah and recently gave the keynote talk, The Confluence of Water, History, and the Public in Utah, at the Utah State Historical Society Conference.

Greg has been director of the American West Center since 2012 but has been involved with the Center since 1988. He received his PhD in history from the University in Utah and taught history at Colorado State University before returning to the U of U. Our students are often found in Greg's annual environmental history course, and Greg frequently serves on committees for students whose research focuses on environmental, public, or Native history.

In October, 2022, Greg spoke to me about the Think Water Utah project, the relevancy of history to the crisis at Great Salt Lake, and his research on Native issues and public lands. Greg also shared some of his personal story, including the childhood road trips that inspired him to leave his home of Plantation, Florida and become a leading scholar of the American West.

Brooke: You are the Keynote Speaker for the 2022 Utah State Historical Society Conference focused on water. What water issues do you explore in your research? How did you come to this topic?

Greg: As a historian of the American West, water has always been something I’ve studied. I was trained in the history of water because it is such an important issue in the West.

The specific project I was asked to speak about for the Utah State Historical Society is called Think Water Utah. That is an initiative of Utah Humanities, and it has been going on for over three years. The origins of Think Water Utah are in this Smithsonian exhibit called Water Ways. For several decades, Utah Humanities has partnered with the Smithsonian to bring traveling exhibitions to the state as part of a program called Museum on Main Street. The idea is to bring Smithsonian programming to small communities nationwide. My role has been to act as a state consulting scholar. I did this first with the Journey Stories exhibit about travel and migration in 2014. Water Ways, though, morphed into something bigger because Megan van Frank at Utah Humanities had this larger vision. She was able to bring in a second Smithsonian exhibit, in addition to the Museum on Main Street program, called H2O Today. For the past two years, those two exhibits have toured around Utah in the midst of pandemic. The focus became bringing these crucial conversations about water to public audiences and providing historical context. I've been doing locally framed lectures across the state—many of them via Zoom during the pandemic—for Kanab, Green River, Vernal, Park City, Hyrum, Wellsville, and a few other places.

Image courtesy of Utah Humanities.

The other big result is a 40-something page essay that Utah Humanities published called Utah Water Ways. The main areas that I looked at were Native history and Native water use, how different that was from early Mormon irrigation and colonial endeavors, as well as water law and fights over how water should be allocated. Late in the essay, I looked at population growth and climate change as the two critical issues right now. They're intertwined. You can't separate the two. Throughout the whole essay, Great Salt Lake was a touchstone. Now, Great Salt Lake is in the news every week. When I was writing that essay a couple years ago, it was getting dire, but it had not quite reached that critical mass yet. There were certainly many people who were pointing to Great Salt Lake, but the legislature had yet to notice.

I also just started working with a couple of grad students, one former grad student and one current grad student, on the next Smithsonian exhibit, which is called Crossroads. It's about persistence and change in rural America, which will also have a water component.

Brooke: As we face the drying Great Salt Lake and other water crises across the American West, what lessons does history give us to plan for this present moment and the future?

Greg: History, of course, could provide context. It shouldn't be thought of as prophecy. I reject that old idea that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. As historians, we never can quite predict how things are going to work out. But I think that history provides a lesson and a context.

A couple things Great Salt Lake points to is the impact of urban growth in the American West. It is not just about agriculture. Agriculture does consume 80 percent or more of the water that is used in Utah, but the growing demand is actually coming from cities and municipalities. There are going to be moves afoot, I'm sure, to transfer water from agricultural lands to urban areas. One of the most controversial water developments in northern Utah is the Bear River Project, which is pretty much on hold right now. Thirty years ago, when the Bear River Development Act was passed, they said water would be delivered by 2015. Now they say the need won't be there until 2045 or 2050. But the Division of Water Resources is still planning on buying up easements, buying land for reservoir sites, and so on. This planning is still going ahead, and that project is only going to serve one thing: urban growth along the Wasatch Front.

Utah is the fastest growing state in the country, and this is where the story of Owens Lake intersects with Great Salt Lake. In the early part of the 20th century, William J. Mulholland, drove the creation of the Los Angeles Aqueduct and it turned Owens Lake into a dry playa, which created horrible air quality problems. That diversion was to feed the needs of an urban area. Globally, the worst-case scenario is probably the Aral Sea. That was largely the result of Soviet-era diversions to feed industrial cotton production. In both cases, you get an ecosystem that's destroyed, and you get impacts on human life through toxic dust. I think it's important for us to say that can happen here as well. A lot of people are currently saying that can’t happen here. We used to say we'd have always have a peaceful transition of power in this country, but that was before Trump. So, the idea that it can't happen here is just an illusion. I think ultimately, that's the reason the legislature finally did act in a provisional way to try to secure an in-stream flow right for Great Salt Lake, a temporary one of up to 10 years. But in a cynical way, it took waking up every morning and having your car covered with dust or your kids coughing, more importantly, for our legislature to say, ‘Oh, yeah, there is a problem.’

Brooke: Beyond water, your work has also spanned other issues throughout your time as Director of the American West Center. What has this role entailed, and what other topics have you researched?

Greg: I've been director since 2012. But my time here at the Center goes back 35 years. I came to the University of Utah in 1987 to pursue a PhD and work with Richard White—a very famous historian in the American West. I was here to do Native history essentially. The American West Center has a long-standing history of working with tribes in the West going back to the Doris Duke oral history project in the 1960s. In 1967 the American West Center started managing that project. So, one of the first things Richard White told me to do was go up and visit Floyd O'Neil at the American West Center. I did, and I started working for the Center in June of 1988.

Greg Smoak and Floyd O'Neil in the American West Center. Courtesy of University of Utah.

I worked on a series of projects to learn how to do public history. I was editing and recording oral histories and doing contract research and reports for American Indian tribes. A lot of the work I did, especially 25 or 30 years ago, involved the Shoshone Bannock Tribes of Fort Hall, Idaho. We have a long-standing relationship there. That work strangely is coming back to us now. We have request for another project through the Department of Energy to do a land use study of Shoshone Bannock traditional lands, which are part of the Idaho National Laboratory, a nuke site where they've tested reactors since World War II.

I spent some time away at other schools, but when I came back to Utah, I became a co-PI on a project for Shoshone Bannock Tribes again and then started directing the Center. We moved in the direction of public lands history because there were opportunities for contracts and grants with the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the US Forest Service. But some of those are still Native focused. I did a project several years ago for Navajo Nation and the Park Service at Pipe Spring National Monument, which was an oral history project that tried to recover Navajo understandings and family stories dating back to the 1860s. That was not an easy thing to do, but I did come up with one oral history interview with family stories of a Navajo raid on Pipe Spring Ranch in 1866. Those Navajo understandings of that period reshaped the understanding of those events and influenced the origin story of that national monument.

We've just launched a new project with the National Park Service to gather stories about Native understandings and interactions with the Overland Trail segments here in the state of Utah. It's a pilot project tightly focused on the Mormon Pioneer, Pony Express, and California Trail segments within Utah. But it involves tribal consultation, which includes Shoshone Bannock tribes in Idaho, Eastern Shoshone in Wyoming, and then five different tribal groups here in the state of Utah. We’ve also got this ongoing mapping project called the Native Places Atlas.

Greg Smoak in his office at the American West Center. Photo courtesy of the Center.

Brooke: A lot of our students, especially in recent years, have been interested in doing research with tribes. What recommendations do you have for these students?

Greg: First and foremost, listen. Don't approach tribes like you’re the outside savior who knows what they need. Listening goes a very long way. I also think it takes persistence. It's not something that can happen overnight. White people have wanted stuff from Native Americans for a very long time. They’re used to people saying, ‘I've got a great deal for you’ and ‘I want this from you.’ That's a counterproductive way to approach it. You have to establish relationships. That takes repeat visits. It's not just a onetime visit. Email? Not so good, right? A personal phone call following up on an email is certainly a way to start to make contact. If you're just trying to extract something from someone through an email, that's not going to work. So, listen and take it slow. I always tell my students, even if it's a project that benefits a tribe, you need them, they don't need you. I don't mean that in a mean cynical kind of way. But people are busy, and they've got other things that they're doing. Tribal governments have all kinds of things in motion that can't just stop for you.

Brooke: How long have you been affiliated with the Environmental Humanities Program? What drew you to the program?

Greg: I came back to Utah in 2010, and I immediately had a meeting with Steve Tatum, who I'd known many, many years earlier. Steve did his PhD in the English department and had joined the faculty when I arrived as a graduate student back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. I played against his softball team, The Enchiladas. They used to crush us. When I came back to Utah, he was the director of the Environmental Humanities Program, and he asked to meet with me because environmental history was something they wanted to have for students. I started teaching it, and I've taught it every year since, except last academic year I switched to a graduate course in the American West. I teach environmental history as an undergraduate and graduate course, and every year I'll get a couple of EH students in the graduate section.

The environmental humanities is something I've always engaged with in my work with tribes and land use issues and sovereignty. That’s a big part of what students in the program have been doing like Hannah Taub who worked with the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation last year. I think environmental history is a core component of the environmental humanities.

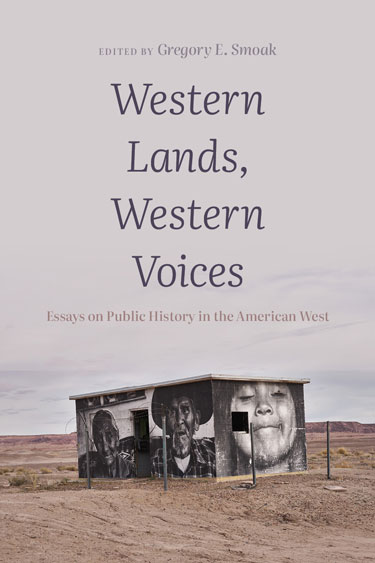

Inspired by the 50th anniversary of the American West Center, Western Lands, Western Voices was edited by Greg Smoak and published in 2021.

Brooke: How did you become interested in studying the American West? Did you grow up in the West?

Greg: I did not. I grew up in South Florida. I was born in Orlando. I grew up just outside of Fort Lauderdale in a town called Plantation. Can't make that up—it's actually called Plantation, Florida. My brother and I loved the outdoors. We were Boy Scouts but camping in Florida is camping in a swamp. We became fascinated with the American West. My mom would take us to the Audubon Film Festival that would run in the winter and feature amateur filmmakers. I had a strange family life. My father was killed in a construction accident when I was two years old. My mom raised us alone, and we didn't have a whole lot of money. But we had a 1971 Volkswagen campervan. Starting in my high school years, we would drive all the way across country with the three of us and however many dogs we had at the time. We visited all these national parks, and I started buying books on Western history and Native history. We’d always end up at the Colter Bay Visitor Center in Grand Teton National Park where there is a Plains Indian Museum. There was a Lakota Sioux artist who would be painting, and it seemed that every summer, there would also be this guy named Laine Thom, who is a member of the Skull Valley Goshutes. I still see him every once in a while. He will come up to the Bear River Massacre Commemoration and read names of people who were killed.

Those road trips got me interested in doing Western history. When I finished my undergrad degree in Florida, I went to Northern Arizona University for my master's degree and then eventually ended up here in Utah doing my PhD. I really don't want to be anywhere else but the West. Many members of the Western History Association teach in places like Connecticut, Maine, Missouri, Maryland, Georgia. I just can't do that. I've been lucky in my academic career. I’ve had two tenured jobs, and the farthest east I had to go was Fort Collins, Colorado. It’s very limiting in the academic world to only apply for jobs in a specific region, especially a region with far fewer people and fewer universities. Pennsylvania has as many four-year universities and colleges as Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, and Nevada combined. So, you limit your options. But living in the West was important to me. Quality of life has always been as important as the job.

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- alumni (4)

- snow (1)

- winter (1)

- climate change (2)

- writing (4)

- creative writing (1)

- book (1)

- memoir (1)

- Great Salt Lake (6)

- symposium (1)

- event (1)

- community engagement (8)

- water (3)

- faculty (5)

- research professor (1)

- history of science (1)

- coevolutionary studies (1)

- American West (1)

- history (1)

- Native history (1)

- public history (1)

- energy (1)

- art (2)

- environmental justice (3)

- just transition (1)

- student (3)

- Great Salt Lake Symposium (1)

- Indigenous (1)

- practitioner-in-residence (2)

- narrative strategy (1)

- political science (1)

- communications (1)

- Mellon Community Fellowship (1)

- environmental health (1)

- air quality (1)

- disability justice (1)

- philosophy (1)

- science (1)

- Anthropocene (1)

- West Desert (1)

- Pony Express (1)

- bicycling (1)

- environmental communication (1)

- queer ecology (1)

- wildfire (1)

- climate communication (1)

- science communication (1)

- forests (1)

- Indigenous sovereignty (1)