Community Engagement Spotlight: Olivia Chandler

**Update** In February 2025, the College of Humanities just featured Olivia's research and success in a graduate student spotlight!

Olivia (she/her) was born and raised in a small town in Upstate New York, and attended Hamilton College for her undergraduate education. Already passionate about political organizing and climate change, Olivia found the convergence of political theory and the environment to be deeply inspiring. During her time at Hamilton, Olivia completed two research projects exploring capitalist alternatives, environmental education, and activism at the East Wind Intentional Community in Missouri and the Tidelines Institutein Alaska. She sought to join together her research and activist work in her involvement in climate justice and divestment organizing on campus. These explorations culminated in a thesis on the praxis of social ecology’s communalism, in an effort to illustrate the potentiality of environmental theory to inspire and inform a liberated future.

After graduating Hamilton in 2023, Olivia spent her summer leading camping trips in the Rocky Mountains before moving to Utah to start the EH program. So far, Olivia’s work has explored the role of alternative education in environmental activism, the relationships between capitalism and climate justice, and the political ecology of the Nature Center at Pia Okwai. She also teaches undergraduates as a Writing Instructor, and works with the Wasatch Mountain Institute facilitating positive outdoor experiences with elementary schoolers. Beyond school, Olivia enjoys hiking, camping, discovering new coffee shops, and spending lots of time exploring the Salt Lake Valley with her cohort.

- Can you tell us about your Environmental Justice Class with the Nature Center at Pia Okwai? Why did you develop this course and what themes did you bring into the design?

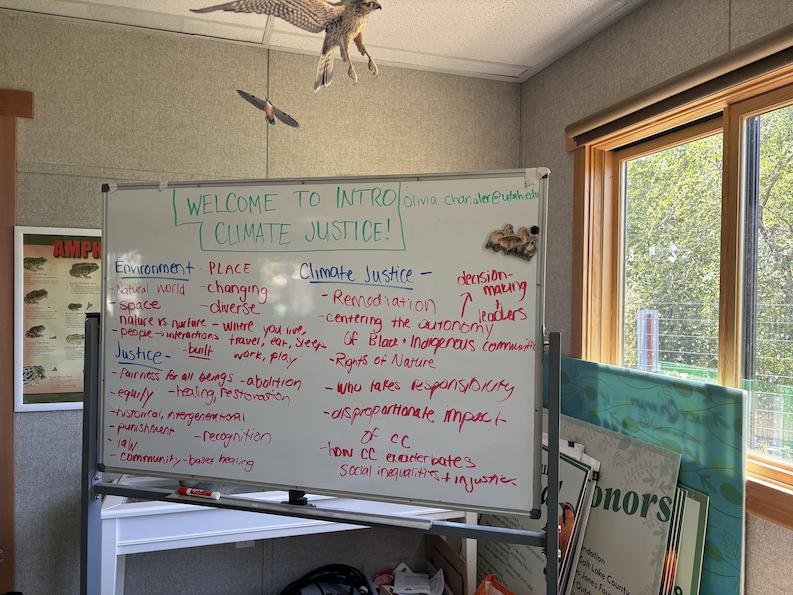

Over the summer, I designed and facilitated two classes as part of the Nature Center’s “Ecojustice” education series. Each class met four times over a month, and were free and open to any community members. The first class was Environmental Political Philosophy, and the second one was Introduction to Climate Justice. We engaged with a variety of materials each week around a specific topic, including podcasts, academic articles, and news/journalism pieces. While the materials were recommended to be read before each class, I also wanted everyone to be able to contribute to discussion if they hadn’t had the chance to engage with the materials. My goal for the courses was to use the time to explore, unpack, and investigate various schools of thought and activism, and connect them to our lives. We worked to cultivate an understanding of the intersections of economic, political, social, and environmental issues. While many of the class topics were rather heavy, concerning climate change and injustice, we always ended by looking towards present activist work and the future– what hope, roadmap, or vision can an intersectional climate justice practice provide? How can we engage in the fight for a more just, liveable, and liberated future for everyone?

When designing the syllabus, I tried to root each week in local issues. I aimed to illuminate the connections between theory and practice– or praxis. Our lived experiences inform academic theory as much as these theories create and explain our lived experiences. By presenting both academic articles and non-academic materials that converged around the same themes, I tried to illustrate that reciprocal relationship. Through discussion questions, I encouraged folks to bring their personal experiences and prior knowledges into the conversation. The classes were discussion based, in an effort to co-create knowledge and the experience as much as possible.

While designing the courses, I was inspired by various theories of radical and critical pedagogy, including from folks such as Ivan Illich and Paulo Freire. I wanted the courses to be accessible to as many community members as possible, which is why it was free to attend and food and childcare were provided. The courses were held in the evenings and weekends to try to align with different work schedules. I was inspired by these critical pedagogical ideas of mutual learning networks that exist outside of an academic institution– what happens when you get folks in a room, completely voluntarily, to discuss and learn together about a topic that matters to them? That they have a real stake in? I tried to let the participants really lead the discussions and shape the course. In the first meeting of the Climate Justice class, I passed around a sheet of paper where everyone could mark down which topics and issues they most wanted to focus on. I used that input to shape the rest of the syllabus and adjusted it week to week to continue incorporating feedback. In designing the courses, I was also considering how I could use my position and privilege as a student and faculty member in a higher education institution to benefit the community more– both through the sharing of knowledge, connections, material resources and time. How can we take learning off “the hill” and use it as a means of community-building and empowerment?

- In what ways do you incorporate principles of environmental humanities into your community engagement work, and how do these principles shape your approach to addressing environmental issues?

It’s funny, because this question first makes me grapple with what environmental humanities even is. Whenever I am asked what I study, I struggle with the answer a bit. I see environmental humanities as a way to use humanities tools and lenses to address environmental issues, but it is also so much deeper than that! The biggest principles of EH that resonate with me are community-engagement, cross-issue solidarity, and interdisciplinary approaches to understanding systems and structures. The very nature of these principles demands that EH, as a field, is in constant conversation and evolving relationships with our community– both within and beyond the academy, as well as with our non-human environment. Because of its rootedness in community and commitment to interdisciplinarity, environmental humanities has shaped my understanding of environmental issues as deeply connected to politics and social justice. We cannot address climate change without addressing its relationship to capitalism or colonialism, for example. Without a holistic, system-level understanding of environmental issues, we can risk replicating structures of injustice while earnestly trying to address the issues.

With all that said, I tried to incorporate these principles into the course syllabi. I drew materials from a variety of fields, both academic and not, and grounded all topics in their social and historical context, as well as folks’ lived experiences. I tried to incorporate community members in the building of the course as well as the weekly meetings. Lastly, I aimed to facilitate the connections between issues or systems that might seem unrelated– how is the building of the new prison on the shore of Great Salt Lake related to climate migration? How does understanding the injustices of poor and uneven air quality in the Salt Lake Valley help us better understand the genocide in Palestine?

- Can you share any challenges or successes you've encountered while implementing the course, and how have these experiences influenced your perspective on environmental advocacy and outreach?

The challenges and successes have been numerous! My initial challenge in approaching this project was facing my own insecurities and feelings of imposter syndrome– as a first year master’s student, what makes me qualified to facilitate a class for adults? Would anyone show up? Since teaching undergraduate students this past year, these feelings are nothing new, and I find that doing it despite the fear is the only way to push through. I also continuously worked to decenter myself in this project by bringing in other community members to contribute to the syllabi and class discussion. Designing the course around participant-led discussion also helped decenter me as a “teacher” and more as a “facilitator.”

Of course, gathering the materials week to week presented its own challenges. I wanted the courses to be engaging and fulfilling to folks of all different levels of experience with education and with environmental issues. I didn’t want the materials or conversation to be intimidating to anyone, nor did I want the class to be too repetitive of prior knowledge. Really leaning into participant-led discussion helped mitigate these differences, as well as providing a range of materials to engage with. I also added descriptions to each material on the syllabus, so folks could be informed in choosing what would be most fruitful to spend their time on.

I’ve been thinking about how to measure if these courses were “successful.” The number of folks who showed up week to week decreased, but the engagement and depth of conversation increased every week. Based on class discussions and feedback I received from participants, I believe this was a meaningful experience for many folks. It also helped participants connect to other people with similar interests or motivations, as well as deepened their connections to the Nature Center. It’s hard to measure educational endeavors when you’re intentionally designing it outside the realm of formal institutions, but I feel confident in the strengthening of my relationship to the Nature Center and other community members as a result of engaging in this work together. Leaving every class with a little more hope and a slightly bigger network of community was beautiful.

- Is there any advice you have to students looking to do scholarly community engagement?

Lean on your peers, program-mates, and faculty! These classes were truly a community effort and a culmination of the relationships I’ve been building over the past year. Having consistent feedback and input from my professors and peers, both on the syllabus and structure of the course, was immensely helpful. I relied heavily on my network to run the childcare offering as well, and to join class when it aligned with their areas of research and experience. I also felt really grateful to have the opportunity to become a part of the years-long relationship between the EH program and the Nature Center– I think there is so much value in building and sustaining long-term community partnerships. If there are relationships that already exist between your institution or program and community partners, that’s a great place to start!

Categories

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- community engagement (15)

- student (4)

- nuclear energy (1)

- community practitioner in residence (2)

- practitioner-in-residence (3)

- student spotlight (1)

- Great Salt Lake (1)

- art (1)

- activism (1)

- faculty (4)

- education (1)

- alumni (3)

- environmental literature (1)

- EH research professor (1)

- utah award in the environmental humanities (1)

- indigenous sovereignty (1)

- activist (1)

- downwinder (1)

- staff (1)

- students (2)

- thesis (2)

- project (2)

- exam (1)

- Native research methods (1)

- 1U4U (1)

- graduation (1)

- research (1)

- event (1)

- youth activism (1)