Faculty Feature: Katharina Gerstenberger

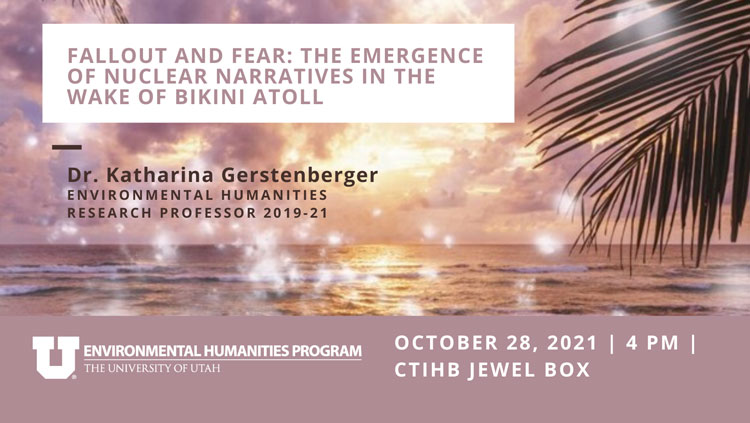

Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger is Professor of German in the Department of World Languages and Cultures at the University of Utah. She served as the interim director of the Environmental Humanities Program for the 2020-2021 academic year. She also served as department chair for World Languages and Culture from 2012-2018. Katharina was the 2019-2021 Environmental Humanities Research Professor, and she is currently a Virgil C. Aldrich Faculty Fellow with the Tanner Humanities Center. She is researching and working on a book about nuclear narratives. Using examples from different countries, including Germany, the U.S., and the Marshall Islands, Katharina looks to literature, visual art, and film to trace the emergence of nuclear narratives that originated with nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll. On Thursday, October 28, 2021 at 4 p.m., Katharina will present a talk Fallout and Fear: The Emergence of Nuclear Narratives in the Wake of Bikini Atoll.

In addition to her work on nuclear narratives, Katharina serves as Editor of German Studies Review. She is the author of Truth to Tell: German Women’s Autobiographies and Turn-of-the-Century Culture (2000) and Writing the New Berlin: The German Capital in Post-Wall Literature (2008). She co-edited German Literature in a New Century: Trends, Traditions, Transformations, Transitions (2008); After the Berlin Wall: Germany and Beyond (2011); and Catastrophe and Catharsis: Perspectives on Disaster and Redemption in German Culture and Beyond (2015). Her articles on topics of 20th and 21st German literary culture have appeared in numerous journals. She is a member of the Transatlantic Research Network in Environmental Humanities.

In October 2021, I interviewed Katharina about her experience with the EH Program, what drew her to the environmental humanities, and her current research.

Brooke: You finished your term as interim director of the Environmental Humanities Program in June of this year. How was your experience? What did you enjoy?

Katharina: I really enjoyed the whole experience. I felt very privileged when Jeff and the current dean asked me if I wanted to serve as the interim director, and I immediately decided that this would be a good chance for me to contribute to the university and my own research. When I moved to Utah almost 10 years ago, I began to dive into the environmental humanities. I felt that running the program, even just for a year, would give me a chance to connect with other faculty here on campus and with students in the program. When I signed up for this, we did not know that COVID was going to happen, so that, of course required me and everybody else involved to adjust. But overall, I got out of it what I had hoped to get out of it. The Environmental Humanities Research Interest Group was very helpful to discuss books and issues with colleagues. But as interim director, I had a chance to connect with faculty more and get to know them better. I also love working with the students. I taught the Tertulia course, which is kind of small, you only meet every other week. But I learned a lot from the students because it's a different, younger generation. I'm impressed with their energy, their forward-looking projects, their activism—which I have to say is not something that I do, but I very much respect. I was interested in learning from them to understand how they think, how they approach things, their optimism. Sometimes you can think, well, we're in a pretty dire situation here. But the students keep going and try to make their impact where possible. So overall, it has been a good year. I look forward to attending the students’ final defenses to see what came of their work.

Brooke: As a German professor, what drew you to the environmental humanities?

Katharina: I came to Utah in 2012. I was hired as an external department chair for what's now called World Languages and Cultures. Obviously, that kept me quite busy. But I always managed to do at least a little bit of research, in part to balance out the administrative work. I think what happened to me is what happens to a lot of people when they come to Utah. I’d been to Utah before as a tourist going to the national parks. It's just a beautiful place, and that in part drew me to the appointment here at this university. I thought about how I wanted to establish myself here at the University of Utah, and I learned about the environmental humanities program through Jeff. He invited me to the research interest group, and then I became aware of the Environmental Humanities Research Professorship and applied and received that in 2019. I think through the strength of the Environmental Humanities Program, I got more interested in environmental humanities issues and learned about what's going on in Utah. Certainly, we have all this beauty, but it's also really beauty under duress. The more you learn about the place, the more aware you become. I think the latest chapter is the shrinking Great Salt Lake, but that’s only one example, right?

In addition to the place and the strength of the program here, I am trained in German literature and German studies. In Germany, there’s a lot of interest in the environment and a lot of environmental literature. Germany has a strong environmental, green movement. Needless to say, Germany also has a problematic environmental history because the Nazis appropriated the blood and soil idea. So, you must look very carefully into the different texts and interpret them accordingly. But Germany has an environmental tradition. The term sustainability for instance, if I'm not mistaken, originally comes from a German forester in the late 17th century. He noticed that if we keep cutting down all the forests, we're going to be in trouble. So, Germany clearly has a long tradition of environmentalism. I put this together with what I've learned here in Utah, what I was exposed to, and thought maybe I can bring these two together. I'm fascinated by German literature, but in this country, it’s a relatively small field. So, I figured if I could branch out a little bit and bring German literature and environmental humanities together, it will hopefully also allow me to speak to a larger audience.

Brooke: As the EH Research Professor and now a fellow in the Tanner Humanities Center, you’ve been researching nuclear narratives. What are your research questions and key findings so far?

Katharina: I am looking at nuclear sites, both test sites like Bikini Atoll and high-profile accident sites like Chernobyl and Fukushima. My point of entry into this is German literature and international literature. I'm interested in how writers, filmmakers, and visual artists respond to these catastrophes and what happened to the site, to the land, to the people. With nuclear narratives, people were at first more concerned with what happens globally. In the 1950s, people become aware of nuclear fallout and that what happens in Bikini Atoll doesn't stay literally in Bikini Atoll, it also has an effect on, for instance, people in Germany. So, this is my point of entry: How did people become aware of the dangers and then how did they put this into words? Nuclear catastrophes were all new, so artists and writers had to find a new language for this. And then moving beyond the general awareness, I’m interested in how, over time, we begin asking other questions. What happened to the people in Bikini Atoll? What does it mean to live in Chernobyl? Is the radioactive water from Fukushima going to show up on the West Coast of the United States? There’s this back and forth between the local and global. To what degree can you even understand what’s happening locally and address the global concern? That is the tension that I’m interested in researching. I look at German literature, French, English, American, Irish, the Marshall Islands. I’m doing a comparative study that’s chronological over time. How does this discourse change over time? How do people from different locations speak on these issues? What kind of images, both in terms of language, but also film and visual arts, do people come up with?

Brooke: What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

Katharina: I love the outdoors. I'm kind of a modest type of athlete, but I love to hike. I do some biking. During COVID, I rediscovered cross country skiing. I'd done it decades ago as a graduate student, and at first, I didn't even know you could do cross country skiing in Utah. But it turns out you can, so I sort of I dusted off my old skis. I like to travel; you don’t have to travel too far in Utah to be in a beautiful environment. I love to read. I read a lot of fiction, German and American. I'm a big reader, certainly. I love movies. One of my favorite things here in Salt Lake is the Sundance Film Festival. That's about my highlight of the year because you see films that you typically don't get to see, which I really appreciate. Last year obviously it was all online, so I'm really hoping that I'll be able to go again this coming year in person. Slowly but surely, of course, I’m also making new friends here and connecting with people. I’m building a good life here in Utah that's enjoyable and satisfying.

Categories

Featured Posts

Tag Cloud

- community engagement (2)

- student (1)

- trees (1)

- environmental education (1)

- plants (1)

- alumni (1)

- forests (1)

- phd (1)

- policy (1)

- collaboration (1)

- governance (1)

- land management (1)

- forest management (1)

- bikes (1)

- bicycling (1)

- advocacy (1)

- faculty (2)

- energy (1)

- nuclear energy (1)

- literature (1)

- film (1)

- art (1)

- leadership (1)

- research professorship (1)

- research (1)

- nuclearism (1)